Exhibition Gallery

Critical Mass 2024 Top 50 Exhibit

Location: Atlanta Photography Group Gallery, 1544 Piedmont Ave, NE, #107, Atlanta, GA 30324

Dates: Jan. 14 – Feb. 8, 2025, Opening Reception: Jan. 23, 2025, 6 pm – 9 pm

Curatorial Statement: Where Have We Been? Where Are We Going?

Photography has long served as a mirror reflecting our past’s complexities while offering a lens through which to imagine our future. Where Have We Been? Where Are We Going? is an evocative exploration of the temporal, social, and emotional landscapes that define human experience. This exhibit presents a collection of photographic works that traverse memory, identity, and aspiration, inviting viewers to reflect on their personal and collective journeys.

The “where have we been” anchors us in nostalgia, capturing fragments of history—whether familial, cultural, or environmental—that shape who we are today. These images, rich with texture and emotion, ask us to confront the weight of memory and the significance of the moments we carry forward. This section celebrates photography as a keeper of time, from abandoned spaces whispering stories of bygone eras to intimate portraits of individuals frozen in pivotal moments.

Conversely, the “where are we going” propels us into a world of possibility and uncertainty. This section features images that look forward—some with optimism, others with apprehension. Themes of transformation, resilience, and change emerge, offering a visual dialogue on progress, the unknown, and humanity’s ongoing quest for meaning in an ever-shifting world. Vibrant, surreal, and boundary-pushing, these photographs challenge traditional notions of narrative and encourage viewers to imagine unwritten futures.

Together, the exhibition creates a bridge between the past and the future, grounded in the immediacy of the photographic medium. It challenges the audience to reflect: What have we learned from where we’ve been? How can those lessons guide us in where we are going? Through this dual lens, “Where Have We Been? Where Are We Going?” becomes an artistic inquiry and a call for introspection, action, and hope.

Through the interplay between reflection and projection, these photographs underscore the power of imagery to capture life as it is and inspire visions of what it could become.

Polly Gaillard, Photolucida Program Director

Andrés Gallego, New York Interior

In 1992, a number of American photographers paid homage to Hopper in an exhibition linking photography and painting. At the event, Joel Meyerowitz emphasised the fundamental difference between the nature of photography as a momentary event and the nature of painting as a process, but what happens when we unite both languages in the same work?

This project, is made up of a series of photographs represented around Hopper's work, where the views of the windows are created by the artist himself with acrylic paint on canvas, as well as the scenography made on a real scale. We see his wife, just as Hopper depicted Jo. We can think of it as a portrait of her or, as the painter did, we can think of it as a portrait of any of us, a place where we can take shelter.

On the other hand, the choice of subject matter beyond the inspiration in Hopper's work, refers to what Jean-Paul Sartre addresses in the context of his existentialist philosophy. Sartre suggests that the "I" we construct for society is often a form of "bad faith", a self-deception that allows us to avoid the anguish of our freedom and responsibility. In contrast, our authentic 'self' is revealed when we are alone and face our true nature without the pressures and expectations of others.

“Hell is other people"

Mark Forbes, Conversations

These images are from my debut monograph 'Collected memories' (published Hatje Cantz, 2023).

"The more we see imagery of people, places and spaces, the more our individual memories are shaped by the photographs that we choose to hold onto.

As time passes and details fade, these photographs become our memories. As a result when an image is made, explicitly or subconsciously, decisions are being made about how things will be remembered.

While these images are my collected memories, they are here to be shared and possibly become yours too.

The series has evolved over the last 5 years and has coincided with a focus on mindfulness and meditation in my life.

All images were photographed on medium format film.

Good things take time."

— Mark Forbes

In terms of my general approach to photography, I am an image collector. The vast majority of my photos occur organically, very much by happenchance, usually on the way to a different destination. People often comment that my photography gives them a sense of déjà vu and longing, even when they know they’ve never been to the places in the images. However there is something very familiar, something intangible that can be related to. It is this deeper connection with the viewer that I strive to achieve through my photography.

Dirk Hardy, Vivarium, Episode 4, Cinema Il Sogno: La Luna

Vivarium is an ongoing series of constructed dioramas, called Episodes. With his socially engaged tableaux Hardy studies the complexity and coherence of today’s pressing issues. In the creation of these worlds Hardy fuses his imagination, observations, personal memories and true events. Every Episode has its own topic, such as conspiracy thinking (Episode 11), modern working conditions (Episode 9, Free Delivery), racial profiling (Episode 6, On Guard), gender roles (Episode 4 and 5, Cinema Il Sogno) and the regeneration of life (Episode 12 and 13).

Each Episode comes with a project description that can be found at https://www.dirkhardy.com/vivarium.

Vivarium is an ongoing project, started in 2018. Every world you see once existed in Hardy’s studio. For each Episode, he meticulously designs, builds and photographs a new world. Hardy creates meaningful narratives through the use of characters, objects and their composition. The final works are full of detail and displayed life-size - one-to-one - in a window frame, sparking a direct encounter between the viewer and subject.

It takes 3 to 4 months to complete a tableau. By addressing a different topic in each Episode while applying a consistent working method, Vivarium is an expanding multiverse of portals where life takes place.

In addition, Vivarium Self-Portraits provide a glimpse into Hardy’s constructed worlds and working-method. They are rooted in his urge to understand and empathize with his characters.

Christos Palios, Fox Theatre | Spokane, WA

“We sell tickets to theatres, not movies,” asserted cinema-mogul Marcus Loew a century ago. The Roaring 20s encapsulated film, music, and art in the era's mania-fueled excess. Accompanying accelerated development of the movie industry included feverish transformation of traditional theatres into labyrinthine palaces. Americans sought glamour, movies reflected the lifestyle, and egalitarian hearts were ardently captured—the temple of the cinema was born. In my ongoing visits to historic picture-palaces across America, I've discovered shifting consumption of the period reflected broader decorative expression among these fantastical spaces.

As the post-war boom, Jazz Age, Prohibition, and the Depression introduced paradigm shifts, an evolving zeitgeist eschewed classic ornamentation in the spirit of fresh gimmicks and machine-age innovation. To appeal to broader audiences seeking fashionable experiences at minimal cost of entry, aesthetic interpretations expanded. Designers embellished with open-sky illusions, modern lounges, crystal fountains, novel lighting schemes, sound-proof children's playrooms, primitive air-conditioning, and towering crystal fountains, among sundry enhancements.

Long before television, these well-attended ingenious interiors were the highlight of people's week where denizens escaped to socialize and be seen. Redolent of silk damask and poly-chrome plaster combined with electric neon and brilliant cool metal, my senses muse into pure perception as living layers of time weigh defiantly upon this extant architectural grandeur. As economic disparities and excesses inexorably permeate contemporary generations, I ponder the nostalgic relevance of flamboyant artistry and ornamental decadence patrons once sought. These photographs contrast an array of Old World-themed theatre interiors with then-modernistic counterparts of revelry and machine-age prosperity.

Heather Evans Smith, All That My Arms Can Hold

“How many of you have been saved?”, the preacher shouted. The congregation promptly raised their hands. Not wanting to be the sole individual with their hand down, I slowly raised mine to join theirs. Why had this magical experience not happened to me? I desired to comprehend why faith held a deeper meaning for them beyond mere attendance at Sunday services.

As a young adult, I ventured out on my own, skipping Sundays, yet the questions persisted. One evening, I found myself in the living room of my spiritual friend. “How do you believe?”, I asked. She responded with confidence, “You simply must pray for it. You just gotta have faith. That’s all.” Following her advice, I prayed earnestly, hoping for a transformative experience. Nothing seemed to change. Over time, these inquiries faded, but they never completely disappeared. They would resurface during significant events, such as the birth of a child or the loss of a parent. Despite my efforts, I still felt as though I was merely going through the motions, lacking the profound connection that others seemed to possess.

Often, doubters choose to keep their thoughts hidden when they lack unwavering faith. This decision can lead to a profound sense of isolation, especially when surrounded by individuals who are steadfast in their beliefs. These images delve into the memories of those bygone Sundays and the lifelong pursuit of finding answers. How is it that some can wholeheartedly embrace traditional faith while the rest of us are left questioning?

Astrid Reischwitz, Egg Pancakes and Yarn

The Taste of Memory explores personal and collective family narratives woven through still life compositions, intertwining threads of home, heritage, and identity. Through the careful arrangement of ingredients and culinary artifacts, I pay homage to the kitchen traditions that have shaped my family's story across generations. My compositions offer a visual journey through the tastes and textures of traditions inspired by Dutch still life paintings–and the family kitchen table.

Old family recipes from my village in Northern Germany serve as both muse and medium in my artistic practice. In a small farming village, fruits and vegetables from surrounding fields and gardens were preserved for wintertime use. Herbs and sausages were hung from the kitchen ceiling to dry. As memory shifts in the act of recollection, recipes evolve over time, mirroring the dynamic nature of cultural identity. Some of the images include embroidery fragments, reminiscent of old decorative dish towels from the village. These patterns, once created as celebratory symbolism for births, weddings, and funerals, now speak of loss and the gradual disappearance of cultural rites.

Through the arrangements of everyday objects, I evoke the familiarity and comfort of domestic spaces. Each item from my family’s now uninhabited farmhouse holds a story, a connection to the past, and a reflection of the present. The Taste of Memory serves as a portal to the heart of home, a goodbye to a memory lost and an invitation to create a new recipe, a new memory, and a new story.

Kimberly Witham, Champagne Dreams

“. . . like a house of Jan Steen”

-Dutch expression describing a messy or chaotic place

These photographs are my homage to the work of Jan Steen (Netherlands, 1626-79)

Steen’s paintings depict domestic chaos with lush color, immense detail, and ample humor. Parents are asleep or drunk, the children are up to mischief, and the pets take advantage of the mess. I am particularly drawn to the animals populating Steen’s images. While there are monkeys, parrots and exotic creatures; the dogs are my personal favorites.

I have long been a fan of Steen’s work, but in recent years his images resonate more deeply. With my own feral son and two rambunctious dogs, my daily life often seems “like a house of Jan Steen.” The photographs in “The Hounds of Jan Steen” envision pets creating havoc while the adults are out of the room. Making these photographs transformed my studio into a living Jan Steen painting. My well laid plans turning to chaos.

Julia Fullerton-Batten, Amarilla Portrait, from 'Frida- A singular vision of Beauty & Pain' project

Frida Kahlo has become an iconic figure in the art world and beyond. Her unique vision and fearless self-expression have made her a ‘Goddess’ figure whose legacy continues to grow, inspiring new generations of artists, activists, and admirers around the world. Her work is a vivid and complex tapestry that mixes personal suffering, cultural identity, and political beliefs; but it’s her relationship with Mexico that amazes me the most. Her deep love for her country is central to her art, with its heritage manifesting in the themes, symbols, and styles she used. Through her paintings, Kahlo offers us a unique perspective on Mexican culture, identity, and the human condition, leaving an indelible mark on both national and global art history. With the help from local people in Mexico I was given access to hidden and secret locations, such as an abandoned mansion right in the heart of Mexico City, a private residence designed by the internationally renowned architect Luis Barragan, ancient haciendas steeped in history and the creepy doll island on Xochimilco, famous for its floating gardens and full of mysticism.

Kazuaki Koseki, Courting Soul

For my series, I explore the relationship between ecology and the natural environment of "HImebotaru" flying in the summer night forest.

The spectacle of fireflies, an endemic species of Japan, flying through the summer forest is just like the twinkling of stars in the sky, just like the brilliance of life for just 10 days.

The forests they live in include forests that have been replanted by clearing old virgin forests, and some forests left behind after clearing virgin forests for development.These places also have a connection with Japanese nature worship, and are familiar with “Shinto”, which believes in “animism”, an ancient Japanese way of thinking that feels God in all things.

I have been observing the ecology and habitat of Himebotaru in the forests of Yamagata Prefecture for many years, and have realized that the repeated light of fireflies is stored in my brain over a longer unit of time, rather than just for a moment.

Create a story by capturing reality and adding subjective perspectives and sensations, such as emotion and awe of mountains and forests.

Alteration and damage caused by deforestation, natural disasters, climate change, and exploitation of wild places by tourism and industry. The mesmerising light and awe-inspiring images of the forest at night suggest the need to protect the forest.

The unpredictability of the fireflies' trails of light suggests concern about the urgency of our planet's climate crisis, while at the same time holding a strong and enduring hope for the future.

Xuan Hui Ng, The Sound of Snow #27

Diamond dust are ice crystals that form in the air when temperatures dive below about -3 deg F (or -16 deg C) overnight. When skies are clear, heat from the ground escapes and the air nearer the surface becomes colder than the air above. The warmer air transports moisture to the air below. When there is sufficient humidity, ice crystals will form. On calm mornings, these ice crystals sparkle like light bubbles in the sunlight for a few precious minutes before they melt away and disappear.

Over the past few winters in Hokkaido, Japan, sightings of diamond dust became increasingly rare. The temperatures were generally higher and weather patterns were more erratic, rendering conditions unfavorable for diamond dust formation. Even when diamond dust appeared, they were sparser and even more short-lived. My fear that this breathtaking phenomenon may someday vanish completely has led me to pursue it in greater earnestness.

I hope that my photographs can prompt people to be a little kinder towards the environment so that they will not be a mere record of their once brilliance.

Matthew Ludak, An American Home

Nothing Gold Can Stay is a documentary photography project that takes a closer look at how economic globalization has left its mark on former industrial cities and struggling small towns across America. Inspired in part by my own family history of living and working in a small mining town in Wester Pennsylvania, this project delves deep into the intricate tapestry of economic desperation, resilience, beauty, and transformation that defines these often-overlooked corners of society. Additionally, the project aims to draw attention to the environmental impact wrought by the steel and coal industries, examining the lasting consequences on the landscapes and communities that once thrived alongside these industrial giants.

The protagonists of the project are the small towns and rural communities that once hummed on the pulse of factories, mills, and mining. Nothing Gold Can Stay examines the interplay between economic shifts and the lives of those who have weathered the storms of change. Image by image, the project seeks to capture the timeless essence of these communities, revealing a quiet beauty in the still moments of everyday life.

Ultimately, this project serves as a reminder that within the ruins of the past lie seeds of renewal and growth. Nothing Gold Can Stay implores us to cherish the moments of quiet beauty that remain amidst the march of progress, and to honor the resilience of those who have faced adversity, uncertainty, hardship with unwavering grace.

Jacques Gautreau, Quick Stop, Knoxville TN

Tennessee roads hold artistic significance as the real and symbolic links between diverse ethnic and spiritual traditions ranging from the Appalachian mountains around Bristol to the Mississippi river flats around Memphis.

I am creating a body of work documenting the cultural and physical landscape of Tennessee - along its urban, suburban, and rural pathways - from the point of view of a European-born person living in Tennessee

As a French native who is also an American citizen living in Tennessee, I am constantly reshaping my own perspective of my adopted surroundings as I transition more from being a European to being an American, and by allowing the values I brought with me to be enriched or impeded by my new environment.

My photographic vision has evolved along with that experience. Meanwhile, my new country - and especially the state in which I now live - has encountered fast transformation on many fronts. I am trying to create a visual chronicle of the unique time and place in which I now travel, through the observant lens of a stranger looking at the lay of the land.

Jim Hill, Phone Home

Small Places (2022-2024) provides a visual connection to contemporary life in small agricultural towns in Illinois and Iowa. I lived in a small Midwestern farm town for eight years but was always considered a newcomer. The feeling of community in small towns, where people know each other well, perhaps too well at times, is unique in my experience. While feeling a connection to the community, there is also a contradictory feeling of isolation.My world was limited and it felt like a long way to anywhere. Small Places is a way for me to better understand and honor a part of my life that passed when I moved back to the city.

I have systematically wandered through over 150 small towns in central Illinois and Iowa to capture the abundance, the beauty and the isolation. Illinois and Iowa consistently lead the United States in corn and soybean production, yet the small towns in the region continue to lose population. As farm production becomes more consolidated and big box retailers drive local merchants out of business, the small towns in the region struggle to reinvent themselves amid an agricultural bounty.

Small Places was purposely shot mostly at night. At night, the lit up grain elevators tower over the surrounding towns, providing a visual metaphor for the abundance of the region. The darkness of the rural midwestern sky provides a backdrop which accentuates the isolation of the small towns and transforms the mundane into the beautiful.

Matt Eich, Calling the hounds, Alabama

This submission is drawn from a monograph containing 91 photographs made between 2006 - 2018, published by Sturm & Drang in July 2024.

It is 2024 in America. I am 37 years old.

Through the course of making these photographs, my relationship to America and the medium of photography has grown heavier. What was once a creeping feeling, a gnawing worry, has now been made fully visible. My country is broken, and I fear it may be beyond repair. If you still believe the myth, you aren’t paying attention.

The America of these photographs is gone, replaced by something darker, more paranoid, more self-destructive. For many it has always been a difficult and unjust land. When I look at these images, I think about how quickly time passes, how soon we will all be gone from this earth. And life will go on, in all its beauty, all its terribleness. I think about how heavy it feels to move through this world, but how light my efforts are when made tangible in the form of photographs. They are light as air. Like smoke. Unable to change a damn thing.

Despite my predisposition towards despair, I hope that America’s arc can drift towards peace, justice, equity, and sustainability. While the photographs are inextricable from how I feel, they are meant to be about something more—a search for a shared humanity, an intimacy with strangers, the desire for an expanded empathy.

Bryan Birks, Doug

Articles of Virtu is an ongoing project that explores the intimate relationship between the people of the American Midwest and the cars they own. Capturing the individuals, the land in which they live, and the interiors of their homes and garages, this series aims to showcase the unique identity and culture shaped by the automobile.

Old and young, the people I photograph all have thoughts and ideas about what will come of their lives and the things they own. The amount of time I spend with each person varies. It can be short, long, or over multiple encounters that span years. Conversations around legacy always unfold, and in doing so, just before we part ways, they always end with a goal of some sort, whether to fix the motor of the abandoned Riviera or possibly touch up the chipped paint. They take a small pause, look over the car one more time, and say, “Maybe one day.” We go our separate ways, the car is covered back up, and the only thing that changes is the sun’s position in the sky.

Stefanos Paikos, Beach Holiday on Lampedusa

In Europe, the discussion often focuses on refugees who have already reached the mainland. But what happens before they arrive? Attention typically shifts to them only once they have officially arrived and been granted asylum. This selective perception resembles a game show: only those who reach the final are noticed and rewarded. The others, who drop out earlier, quietly disappear from view—in the reality of fleeing, this often means losing their lives.

In 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic and following the catastrophic fire in the Moria camp, refugee stories barely surfaced in the media. How do these individuals reach Europe? What routes do they take, and what transpires along these paths? These questions lingered. That year, I met Milad Ebrahimi in Hamburg. Our conversation unveiled his arduous journey from Iran through Turkey to Germany. His story inspired me to delve deeper into the hidden migration routes to Europe.

Motivated by Milad's experiences, I initiated a project to trace migration routes from their endpoints in Europe back to their origins. I am currently following two primary routes. One route traces the journey from Greece, through Turkey and Iran, to Afghanistan. The other route begins in Lampedusa, Italy, and extends to Central Africa. This project aims to develop a deeper understanding of the real conditions of people on their perilous journey and to tell the often overlooked stories.

Aimee McCrory, Making Out

ROLLER COASTER; Scenes from a Marriage is a cinematic body of work addressing the complexities and challenges in long-term relationships. In our culture, growing old is often accompanied by feelings of shame. Terms such as ‘losing your wits,’ ‘becoming irrelevant,' and ‘being abandoned’ often haunt older individuals. My goal as an artist is to raise awareness regarding the joys and challenges of growing old together. It was the height of the pandemic. My husband (Don) and I were quarantined in our home. People our age were constantly being plagued by concerns surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic and I was experiencing a lot of anxiety. I decided to channel those intense emotions through making photographs. Over a period of weeks, it became clear to me that within our four walls I could create an infinite number of scenarios that illustrated the elements our marriage. My primary intention was to expose what it looks like to manage a relationship in our seventies. The process was a vigorous physical and emotional challenge that also required my husband’s participation. Getting his compliance was not always easy. Each time I prepared for a scene, I had to check lighting, focus, angles, and gestures and set the emotional tone. It would take me anywhere from days to weeks to manifest my vision. The making of the work has added a new depth to our marriage. Art Publisher Kehrer Verlag (Heidelberg, Germany) has released my first monograph: Roller Coaster; Scenes From a Marriage.

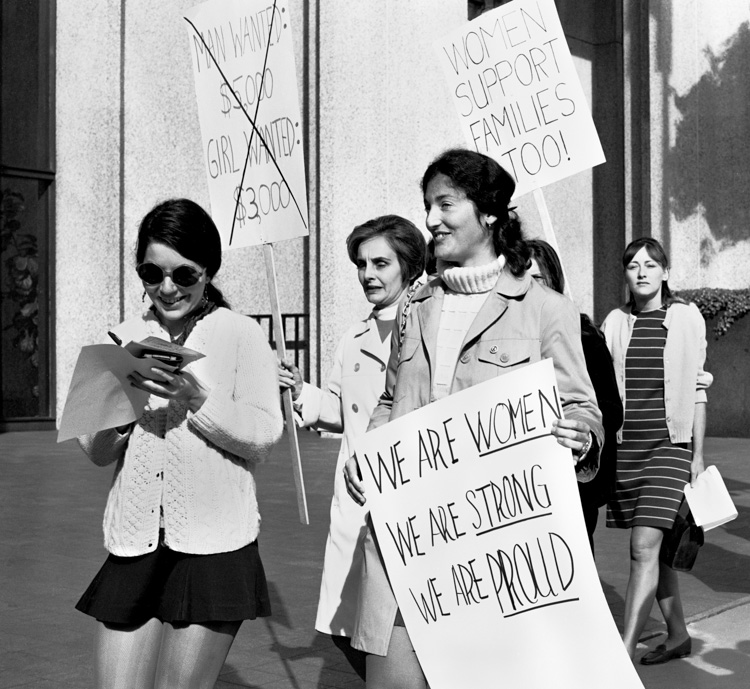

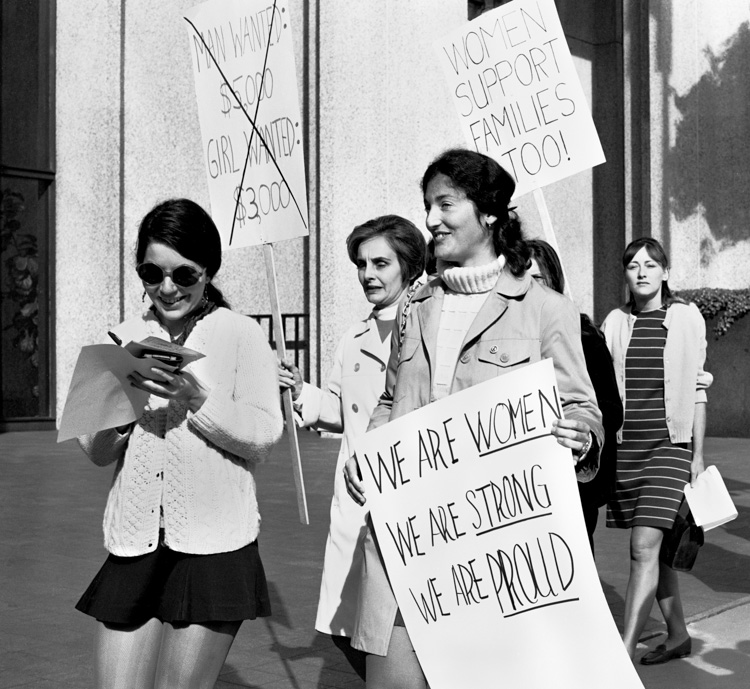

Nina Hamberg, We Are Strong

Change Has a Female Face is a work of historical black-and-white images documenting the early 1970s Women’s Movement. Shot from 1969 to 1972 in San Francisco, it explores a part of the feminist struggle that has never been portrayed. While images of national leaders and large demonstrations are widely circulated, we haven’t seen the small protests and private gatherings that were at the heart of the movement.

I began this project when I was twenty-one, an undergraduate fine-art photography major and an activist fighting sexism. I wanted to capture a visual record of who we were and what we did, one that merged fine art photography and photojournalism. Over the next three years I shot 1100 images of the women’s movement. I also saved every feminist newsletter and flier I obtained.

These archives are survivors. They’ve travelled with me for fifty years, waiting to be seen. Five years ago, I reviewed the images and selected 100 for multiple purposes. Those images, scanned as large 16-bit TIFF files, form the core of Change Has a Female Face. The project also includes 11”x14” digital prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta, 8”x10” silver gelatin prints on Agfa Brovira produced in my 1970s darkroom and extensive feminist ephemera.

Change Has a Female Face was created to capture the story of 1970s grassroots feminism. That remains my goal, but it’s now infused with urgency. With women’s rights under coordinated assault, I hope this project inspires the people who steer our present and shape our future.

Margo Cooper, Through the Window

A third of low-income households in Maine are headed by women [Maine Development Foundation]. Some became mothers as teenagers, raising children as single parents at various points along their journey. These women often endure trauma, addiction, and/or health issues while managing their family’s lives.

My photographs capture the intimate moments of daily life and the dignity of struggling families. Through my lens, love and affection reveal themselves in ways large and small despite the hardship. Cora’s story is one of determination, devotion and commitment to her family.

I continue to photograph Cora, her children and grandchildren.

Lisa McCord, Women in Car

Rotan Switch documents life on my grandparents’ cotton farm in the Arkansas Delta community of Rotan. It takes its name from the community’s central landmark – the railroad switch where farmers loaded their cotton bales onto trains headed out of the Delta. Although it has not been used in years, it remains a potent symbol of the complex intersections of industry and agriculture, of racism and injustice. This project spans forty-five years, from 1978 to present day, following five generations of a community. These photographs are complicated; they exist in the context of the socioeconomic structures of the rural South. Although the subjects are family to me, as a white photographer and the granddaughter of a landowner, my photographs of the Black community implicate my own role in reinforcing these power structures. In a community in which most people spend their time working or caring for children, my ability to observe and document in itself has been a position of privilege. I’ve lived in many places, but my idea of home remains firmly rooted in the Arkansas land and people. I've come to realize that all the photographs I made at Rotan are explorations of home. I’ve also come to realize that the place I call home is not perfect. These images are a record of my story of Rotan, a story that is specific to my and my family’s role in a place where inequities exist to this day. I have done my best to acknowledge this complicated history.

Amy Gaskin, Car Full of Marilyns from the series The Legacy of Marilyn Monroe

Rotan Switch documents life on my grandparents’ cotton farm in the Arkansas Delta community of Rotan. It takes its name from the community’s central landmark – the railroad switch where farmers loaded their cotton bales onto trains headed out of the Delta. Although it has not been used in years, it remains a potent symbol of the complex intersections of industry and agriculture, of racism and injustice. This project spans forty-five years, from 1978 to present day, following five generations of a community. These photographs are complicated; they exist in the context of the socioeconomic structures of the rural South. Although the subjects are family to me, as a white photographer and the granddaughter of a landowner, my photographs of the Black community implicate my own role in reinforcing these power structures. In a community in which most people spend their time working or caring for children, my ability to observe and document in itself has been a position of privilege. I’ve lived in many places, but my idea of home remains firmly rooted in the Arkansas land and people. I've come to realize that all the photographs I made at Rotan are explorations of home. I’ve also come to realize that the place I call home is not perfect. These images are a record of my story of Rotan, a story that is specific to my and my family’s role in a place where inequities exist to this day. I have done my best to acknowledge this complicated history.

R.J. Kern, Winona County Fair King and Queen, Minnesota, 2023

After the Ramsey County Fair in St. Paul, Minnesota was canceled in 2021, I asked fairgoers at other fairs what they would miss most if it were their last year. A common response was the 4-H animal shows, highlighting deep-rooted connections between communities and agriculture.

Rural communities in the U.S. are undergoing significant transformations, with the number of retiring farmers increasing while new farmers are on the decline in Minnesota. As a parent, I am troubled by what this means for the next generation’s understanding of farms, sustainability, and stewardship of the land, especially in the face of climate change. These worries, coupled with the dwindling interest in agriculture among children, motivate my artistic endeavors.

The shift from small family farms to large monoculture operations has had a profound effect on rural America, with county fairs being one of the casualties. Once a vibrant showcase of diverse livestock, some county fairs now see sparse entries in competitions once fierce. Despite diminishing appeal of county fairs to today's youth, these events remain crucial in passing on life lessons and agricultural traditions.

Drawing inspiration from the works of Bruegel and Grandma Moses, I use a large format camera and studio lighting to capture the essence of contemporary agrarian practices at these remaining country fairs. Through the lens of “in-camera photography,” I aim to shed light on the evolving face of American farming and the importance of preserving its heritage.

Mona Bozorgi, Abscission

Threads of Freedom intertwines materials and narratives in photography to question traditional representations of women in the Middle East. This project shares stories of Iranian women using the photographs they have taken of themselves during the recent uprising and protests in Iran. At the time, photographers were prohibited from documenting the uprising, and many who tried to take photos were arrested. So, selfies became a way to document and resist. Women photographed themselves while removing and/or burning their headscarves in the street to show defiance and to reclaim the public spaces that had been stolen from them for almost a half-century.

I conceived this project and its process as a form of protest, a way to resonate with the struggle. Residing outside my country and unable to participate in protests, I found myself overwhelmed and empowered by the images of young, brave women. I collected and printed their images on silk and dismantled the fabric by removing individual threads by hand. Then, I layered the images to create new compositions and to reveal and connect the stories embedded in each photograph. Throughout history, fabric was utilized to simultaneously conceal, beautify, and objectify women's bodies. In Iran, women's bodies and hair have been veiled with fabric for centuries. In Threads of Freedom, fabric becomes a surface that reveals women's bodies instead of covering them, and the threads of the fabric reweave their shared stories.

Takeisha Jefferson, Harvest

"Testify" is my witness to the intricate complexity of American history, particularly the Black experience. As a Black woman and artist in America, I've long grappled with the power of narratives and how they shape our understanding of history, identity, and belonging.

Growing up, I realized that narratives often overshadow truth, especially regarding the history of people of color in America. This work challenges these simplified narratives, inviting dialogue and deeper understanding. Through pieces like "Irrefutable" and my family-inspired collages, I explore the intergenerational impact of our history.

By repurposing books on the Confederacy and Civil War, I mirror current attempts to restrict access to certain historical narratives, challenging us to think critically about the information we consume. My own family history, tracing back generations on this continent, embodies the complexity of American history and our right to belong.

"Testify" isn't just about the past; it's about how we engage with history today and shape our future. In an era of media saturation, critical thinking is crucial. As an artist, I believe in art's power to challenge perspectives and inspire change in ways that differ from academic or political approaches.

Joseph Kayne, The Pueblo Madonna

Using a careful selection of contemporary tintype images that combine contemporary elements and a way of posing with those of traditional elements, I strive to portray Native Americans in or transitioning between their two worlds; traditional and contemporary. Some of the work may be a citation to Edward Curtis’s work, but the project seeks to accurately and honestly portray present day Native Americans. Natives collaborated with the work, and were given the choice on how they wanted to be portrayed, and what clothing or regalia to wear. Unfortunately, the general non-native knowledge of Native Americans is still mostly rooted Hollywood stereotypes media, sports mascots, and in school room half-truths. The result is an unfaithful narrative. From a young age, most people in the United States have been immersed in the current dominant narrative about Native peoples. It’s a largely untrue and deficit-based narrative, as it focuses on challenges and weaknesses, rather than on strengths, positives, and opportunities. These narratives are almost always created by non-Natives, often with the intention to oppress Natives and their cultures. The effects are damaging, leading to poor self-image, suicide, alcoholism, and lack of individual drive. It also reinforces negative stereotypes among non-Native people, thus often shaping thought process and actions. In my work as a photographer, I have learned directly from Native Americans. I am a recognized ally and accomplice in collaborating on portraying the truth of today’s Native Americans. I’ve had the privilege of chronicling their lives “living in two worlds,” that of traditional and tribal culture, and that of modern civilization; and sometimes the confusion and gray area in between. In summary, this project is about disclosure, consent, and collaboration.* *full essay available on request.

Raymond Thompson, Jr., Portal# 3.5923 Christ Church, New Bern, NC.

This place-based project utilizes archival fragments, historical ephemera, and my images to expand narratives about the Black experience and our connection to the North American landscape. This work is based on local historical archives of runaway slave ads, lynching news articles, Black folklore, and other location-specific historical events. Maroons were enslaved people who had escaped their captors but did not flee to the North. Instead, they created a life in hard-to-access swamps or the wild spaces between plantations. The survival strategies and techniques the maroons used to survive in the ungoverned space between plantations can be considered "freedom practices." These practices could include practical approaches as well as more spiritual methods. Through these recently reclaimed threads of stories, we can radically re-envision Black people's connection to the American landscape. This project is also a personal. I have chosen to locate this work in the place where parts of my family's origin story begin. Ultimately, this body of work is about my process of learning how to engage with a landscape infused with trauma to produce ways of knowing that exist outside of that paradigm.

Anne Berry, The Cormorant's Message

Ode to Enchantment explores the puzzle of childhood, when magic and reality mingle in a whimsical, sometimes disquieting dance. This body of work includes both the familiar and the uncanny. Each photograph is a portal to a moment suspended in time and space, where the boundaries between reality and fantasy blur. The images are dreamlike and haunting, capturing a world that is both a playground and a labyrinth. I draw inspiration from literature, myth, personal memories and from the children that I photograph. These subjects, often pictured in moments of solitary contemplation or portrayed in surreal scenes, embody the tension between curiosity and fear, the ordinary and the extraordinary. The lack of color in the photographs as well as the shallow focus and quirky characteristics created by antique lenses help to make the images timeless and transport them from reality to a metaphorical realm where anything can happen. I often experience things that are beyond my understanding. I’m always seeking this invisible connection, which touches something eternal, something not man made. I think all great writing and art touches this ethereal and mystical force that exists beneath the mundane and the superficial.

Rachel Portesi, Branches

These images are a response–part intuitive, part deliberate–to a time when the scaffolding of my life seemed to disappear. I assumed that I’d reemerge on the other side of motherhood the same woman, but it felt like suddenly the Rachel I’d been before becoming a parent was irrelevant, gone. I experienced this as a loss, and grieving it raised questions. Who had I become? Which parts of my old self were best left behind?

I was drawn to early the Victorian practice of making memento mori using hair. Art, sculpture, even mementos of the time consistently used tresses of hair to honor both the dead and the living. In my work, I use that idea as a tool for self-reflection. These tintypes are part of an ongoing series of “Hair Portraits” made to honor the parts of myself I have outgrown and those I want to foster. They explore the nuanced transitions in female identity related to motherhood, aging, and choice.

As I engaged with this new mode, my models became conduits of self-reflection–a way to look at the confines of my chosen female role from the outside. And there I observed a post-maternal kind of strength wholly different from the role I’d inhabited before motherhood. Looking at them now, these images on the wall, photographs of elaborate hair sculptures constructed in my studio to change. Parts of myself I choose to leave behind. Others I bring with me.

Colton Rothwell, Untitled (Trophy)

In this series, titled Pearl Road, I draw upon memories to examine my relationship with the cultural and physical landscape of my youth. I was raised for the most part in a town of 700 people in rural Idaho and felt like an outsider after discovering I was gay in my early adolescence.

During my formative teenage years, I was faced with a choice, to conform to the traditional masculine culture of the Western United States – one defined by violence and extraction– or to run away and create my own sense of belonging. It is through this struggle that my relationship with the idea of place emerges, and I question the persistence of the mythology of the West. The landscape provided both solitude and escape when I was with lovers, but also made us extremely noticeable. It is this tension between ecstasy and fear that I hope to convey in my image-making.

Inspired by the structure of post-documentary approaches by photographers in the 2000s and the aesthetics of the New Topographics exhibition in 1976, the work is intended to meander alongside the vast landscape. Like a living diary, the arrangement of staged and found scenes expands upon emotionally charged memories of exploration of not only the land but also sexuality.

Andrea Sarcos, Remember To Forget

Andrea Sarcos was born in Caracas, Venezuela, and moved to the United States at the age of five. She was raised in Florida and unknowingly lived as an undocumented immigrant for 13 years. Her family encouraged her to marry her high school boyfriend to become a US citizen, which revealed a long process of paperwork, interviews, and life experiences that compelled her to consider her role in society and how documentation plays a fundamental part in our lives. Memory and identity are two of many lenses she views her practice through to process and make meaning of personal and collective narratives surrounding migration, dislocation and acclimatization of new landscapes. Andrea’s personal photographic series documents her family’s migration history through Ecuador, Venezuela and the United States. She began the series in 2016 after assisting her grandma’s transition from the earthly realm and then exploring the land where her grandmother had birthed 13 children: Manta, Ecuador. Each year Andrea would return with questions about her family and images made of other migrant families too. With her most recent journey to Venezuela in 2023, she discovered her family’s archive. In the subtle play of characters and stories imbued within the decaying prints, she is recounting generations of migration patterns and the interweaving connections through time and space between members of her family both living and deceased and the lands which shaped them. Andrea’s photographs subtly unfold how migration has influenced family dynamics, shaped our means of communication, and influenced our self-perceptions.

Sarah Mei Herman, Zhiqi & Liang, Xiamen

Throughout her practice, Sarah Mei Herman explores relationships, loneliness, longing, intimacy and the human urge for physical proximity. Probing gently at the things that bridge and divide her subjects, her projects pay close attention to the vulnerability of transitory life stages – from the trials and fleeting beauty of adolescence to the grey areas between friendship and romance. The notion of time is of equal importance to Herman’s work; photographing the same subjects over many years, she charts fluid cycles of transition and evolution, as well as what remains unchanged and unmoving. The approach reflects the artist’s own preoccupation with the passage of time – or the fear of what’s lost in the process.

Solace:

In response to my long-term Touch series, I was commissioned by Emerson & Wajdowicz Studios (EWS) to produce a related project + book about the LGBTQ+ community in China.

EWS runs a photobook series devoted entirely to LGBTQ+ themed stories – showcasing the diversity and complexity of queer communities around the world.

In September 2019, I returned to Xiamen to portray queer individuals and couples, all of whom I found through my existing network in the city. Alongside portraits of each person, and images of the private spaces they inhabit, Solace features interviews with each subject about life, love and their personal fears. Unable to return to Xiamen during the pandemic, I continued the project in the Netherlands, photographing young members of China’s LGBTQ community who had relocated to Europe.

Yvette Marie Dostatni, Puppeteer Samuel J. Lewis II

"My American Dream" portrays an intricate landscape of perpetually shifting identities in America.

What is Cultural Identity in America? "My American Dream" attempts to untangle and explore this question with subliminal and complex visual narratives.

"My American Dream" depicts a vast American landscape of diverse communities connected and divided by languages, culture, and state lines. These complex cultural boundaries and physical identities can determine what an "American" is and aspires to be by race, class, religion, and education.

These images portray a wide range of borrowed, invented, and cultivated identities that seem ordinary in the subjects' eyes but would be viewed differently by outsiders.

I visually isolate how self-expression, personal personas, and cultural costuming can define and decide our lives and relationships, resulting in either connection or disconnection.

Compared to other nations, America is still in its infancy. We have yet to begin navigating the nuances of living in such a vast and diverse melting pot. Attempts to include can be excluded. As a nation, how do we measure inclusivity? What does "real-time" multiculturalism look like outside its Universities and ad rooms? When is the ground ever truly leveled? Collectively, these photographs indirectly examine American principles, such as patriotism or the idea of freedom for all. These images explore the contrariness and contradictions of one's identity and how one might be seen via a larger and more inclusive lens.

Ultimately, my goal is for the subjects to allow the viewer to recognize "The Self" through the diversity of "The Other."

Terri Warpinski, Every Tree Tells a Story

In this lens-based mixed media assemblage and installation work I am interested in unfolding the complex and messy patterns of our species’ impacts on the environment, and our ongoing renegotiation of its value to all forms of life. These works are rooted in the histories and futures of our fragile ecosystem from the examination of land preserves and conservation areas as they undergo a process of re-wilding and ecological recovery, to the imminent death of our glaciers and other tragic losses due to the rapid warming of the Earth.

In connecting, disrupting, and fragmenting lens-based imagery, along with the integration of text in multiple forms, and incorporating found objects and materials, I forge relationships between personal, cultural, and natural histories. Through my work I seek to make visible a state of mind, a way of perceiving and connecting information and ideas across time and space that are not entirely visual in nature; and in doing so, construct a narrative that is multi-stranded and open-ended addressing various notions related to time, observation, destruction and restoration, the accumulation of knowledge, and the shadow of memory.

Katie Shapiro, Hallucinogenic Joshua Tree

For years my project’s concepts spoke through the metaphor of landscape photographs of places where energy can’t be seen, such as vortexes and sacred spiritual locations. As I’ve continued to work through my practice, and especially after having two children and transforming into a mother, I’ve been working through my own life’s traumas and have realized that the root of my interest is still in the invisible. Specifically, the invisibility of the subconscious and ideas around psychology, and particularly Carl Jungs philosophies. This opening in my practice has led me to my current work around the Jungian idea of “the Shadow”, the unconscious aspect of the personality.

Using physical layers for sculptural dimension changes the experience of viewing a photographic image to get closer at what I’m interested in, which is a feeling that taps into the viewer's unconscious (or Shadow), or that unknown feeling that lies beneath the surface of our understanding. In this body of work, I layer images offset from each other on Plexiglas over inkjet prints to represent the idea of a shadow self. The layering of Plexiglas over inkjet prints creates a slight physical and visual distance from the two or three images, representing the shadow or hidden part of oneself. Not only does the distance create an actual shadow, it is a literal repetition of the original image, suggesting the layering and complicated make up of ourselves.

Charlotta Hauksdottir, Resurgence IX

My work seeks to evoke contemplation about our relationship with the environment. For two decades, I've photographed landscapes of my native Iceland, witnessing firsthand the impacts of climate change. This ongoing project is a visual articulation of these changes and by hand-cutting photographs and layering, the work simulates the physical features of the landscape. Some pieces have removed sections of photographs, layered on top of black fabric, representing the erosion of nature, or text from an essay on global warming, serving as a reminder of the dangers we confront. Recently nature's resilience has become a source of inspiration. Drawing from the persistence of life growing from concrete cracks, I cut and layer photographs in a similar pattern. Those pieces signify renewal and hope, a visual testament to nature's remarkable ability to endure. I am also intertwining branches wrapped with photographs and weaving them together, symbolizing both the devastation wrought upon nature and the potential for proactive human intervention.

Seido Kino, The Strata of Time #002

Japan's postwar economic development was driven by manufacturing. Afterward, increasingly skewed toward urban areas and leaving rural areas, the depopulation with declining birth rates and aging society triggered the problems of the increasing devastation of lands and the widening disparities in infrastructure, medical care, and transportation. This work is a photographic visualization of how the high economic growth of the 1960s has affected the typical two regions, Shimane’s village and Hiroshima’s city, just over the mountains.

History is cumulative. Landscapes are the result of someone's hopes and desires in the past. The past is regarded as a continuum of layers with the present, and history is revealed through casual landscapes in the form of uncovering photographs of the present taken at the same point.

What can be learned by digging up the background? Although there superficially appears to be a disparity between the two regions, as Japan moved from a developing country to a developed country, some things were lost in exchange for what was gained in each region. And some things were preserved.

Physicist J. C. Maxwell said, " The true logic of this world is in the calculus of Probabilities, which takes account of the magnitude of the probability which is, or ought to be, in a reasonable man's mind." But we wonder if those who lived in the 60s could have mathematically predicted then what the landscape looks like now. Where the value of growth resides is ephemeral. No one knows the future for both regions.

Sander Vos, In Between the Shadows 3

"In Between the Shadows" is a series of photographs that invites you to challenge your perception of the familiar. Inspired by cubism, the artist breaks down everyday objects and reassembles them in a way that challenges our perception of depth in photography.

Light and shadow play a key role in the works. Vos utilizes chiaroscuro to deconstruct the objects. A vase might be bathed in light while its base remains shrouded in darkness. This interplay isn't just about highlighting form; it's about fracturing it, transforming ordinary objects into something alien and surreal.

As a viewer you become an active participant, piecing together the fragments, navigating the shifted perspectives, and discovering the hidden depths within the seemingly flat image.

Walter Plotnick, Tar Beach (Homage Faith Ringgold)

My photographic collages serve as a metaphor for anticipation, those moments when the unknown is being revealed.

The implied act of opening the boxes, releases the occupants, allowing them to take flight. The people and objects confined within, through the simple act of unfolding, are exposed revealing what was previously hidden.

I try to convey excitement, and energy in images that are playful, expressive, and nostalgically bring the viewer back to the joyful moments of anticipation felt in childhood.

The unusual and dissimilar combination of people and cardboard boxes is visually unified through the repetition of angles. Despite pairing such disparate elements, I bring them together harmoniously to form images with visual impact, and are frankly, fun to look at.

Barbara Strigel, Balancings

In the familiar space of cities, construction zones are insistently visual. They don't hold the weight of our memories and associations the way architectural spaces do so we are free to consider their repetitions of rebar, walls of texture and scrawls of wire from a purely visual perspective.

When I point my camera at a construction zone, my mind moves into a visual language. I look for balance, unity and rhythm in the relationships between construction materials. I'm open to the idea that this kind of visual thinking has value. If we can find harmony in a group of traffic cones, perhaps we can extend that perspective to the wider world. I'm willing to entertain the notion that engaging with shape will connect us to a place.

My collage process allows me to extract and arrange elements of construction zones. I digitally layer fragments of my photographs with scanned drawings, collages, and printmaking experiments to emphasize the visual grace and movement they contain. Construction zones are the forward momentum of cities made visible. In these collages, I present an exuberant and expansive view of urban space.

Kristin Schnell, I Remember You

Of Cages and Feathers: A Photography Series by Kristin Schnell

"Of Cages and Feathers" explores the complex relationship between humans and birds, highlighting the artificial worlds many birds inhabit in captivity and drawing parallels to our own self-imposed confinements.

The inspiration began in Mecklenburg, surrounded by monocultures that offered little habitat for birds. Over time, I took in birds from owners who could no longer care for them, documenting their artificial environments and contrasting them with their yearning for freedom and nature.

The series captures the beauty and diversity of birds within these settings. Colors, shapes, light, and wind create a metaphorical representation of life in captivity, posing questions about freedom and confinement for both birds and humans.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this parallel became clearer as we found ourselves confined to our homes, leading to increased interest in bird feeding. This shift highlighted our connection to nature and the impact of our actions on the environment.

I build wooden sets in the aviary, paint them, and wait to see if a bird interacts with the set. These images are captured in real-time and are not digitally constructed in Photoshop.

This series is a visual documentation and a call to appreciate nature and the creatures we share our planet with. It urges us to reflect on our relationships with animals and each other, emphasizing the importance of mutual respect and understanding in creating a harmonious coexistence.

Selina Roman, XS12

“You have such a pretty face.” It’s one of those innocuous-sounding compliments given to fat people. It’s a compliment where a “but” is implied – because in the absence of mentioning all of me, I realized that something was wrong with me. For most of my life, I’ve occupied a fat body, navigating currents of self-acceptance and hate. In the accidental brush against a stranger or overflowing into an adjacent airline seat, I have always been aware of the politics of space. Even with body positivity movements in recent years, and more visible fat bodies in mainstream media, I walk a line of visibility and invisibility, self-love and revulsion. Accepting and owning my fatness feels like a political, transgressive act.

In this series of photographs, entitled XS, my body unapologetically occupies the space within the frame. Pastel bodysuits and tights transform my fleshiness into new landscapes and amorphous shapes. These cropped images of various body parts such as stomach, thighs and hips become a formal study of the parts of me that society has shunned. With these photographs, I create a quiet resistance that subverts traditional ideas of beauty. I am in control of these images of a body that society tells me is out of control.

JP Terlizzi, Wedgwood Sapphire Garden with Pineapple Beets

Creatures of Curiosity

Love and food have always been deeply intertwined in my family. Whenever you visited, one of the first questions from any relative was, "Did you eat?" For us, the table is not just a piece of furniture but a gathering place where we come together with loved ones to share stories, create memories, and enjoy each other’s company. It's where we make connections. The act of thoughtfully preparing and presenting food or an arranged table becomes a profound expression of love and care.

The Creatures of Curiosity is the final chapter of The Good Dishes series, which began in 2019 and explores the legacy of the things we pass down for future generations to cherish. It draws inspiration from my personal collection of fine china, representing the essence of tradition and the beauty of connections forged through gathering over a shared meal. The lavish visual feast focuses on a range of creatures, such as exotic birds, tigers, cheetahs, snakes, insects, and monkeys. It depicts an eclectic range where the brightness of color, ornately designed and constructed patterns, and unconventional food pairings suggest temptation and indulgence through the richness of nourishment, the opulence of life, and exotic luxuries. I hope my children and grandchildren will one day cherish these items and the memories and sentiments they evoke.

Galina Kurlat, March 19th, (Bathwater, Breastmilk)

Vestige is a series of lumen prints in which ephemera from my body directly interacts with silver gelatin paper, creating a non-representational self-portrait. In these color-scape photograms, the female form, which is subjected to an onslaught of societal pressure and objectification, defies conventional representation, appearing as mark-making and surface disruptions on photographic paper. Lush pinks, mauves, and reds directly engage a "female" palate while subverting the recognizable for the abstract. Throughout the series, the repetition of the circle is not a direct reference to the body, but a nod to its absence.

Lumen prints are a historic photographic process; they are made by exposing silver gelatin paper to light for extended periods. The paper develops outside the darkroom, needing only sodium thiosulfate to fix the image. By making these photograms outdoors, I connect my body to the environment I live in. Day-to-day changes in light and temperature directly affect the individual print's outcome. Although these images resemble paintings, they are fundamentally photographic; the colors and their variations directly relate to the type of paper used, exposure time, and UV in the light source.

This project is a natural extension of my work with figurative and portrait photography. Instead of a classic depiction of my body, these images reinterpret the gaze by eliminating sensuality (the body) for the sublime (abstraction), creating a new self-portrait while challenging representation of the corporeal. These images become a collaboration between process and intention while addressing themes of identity, mortality, and the body from a uniquely

Eli Craven, Bandage For Finger

First-Aid and The Living Anatomy explores an emotional tension between the desire for intimacy and fear of human contact. The project started with a vintage first-aid manual that sat on the bookshelf for around ten years. During the initial Covid-19 lockdown in the Spring of 2020, medical texts and first-aid manuals in my collection sparked new interest. While searching through these instructional books for images of healing and human care, I felt a deep anxiety about the intimacy of the images, particularly the illustrations of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, blood transfusion, and examinations of the body. Looking at these pictures of doctor and patient, healer and the sick, their faces close, almost touching, I realized I had developed a fear of closeness, a fear of medical care, and a fear of human breath. I re-framed the prints using mirrored brass sheets and wood panels to distort, disrupt, and expand the original compositions, creating works that exist somewhere between image and object.

Pamela Landau Connolly, First Day of School

The photo objects of Columbus Drive use vintage potholder looms, family photographs, archival canvas, and cotton thread to retell my childhood in suburban New Jersey during the 1960s and 70s. My process begins by scanning 3” square snapshots and reprinting them digitally on canvas. I cut the enlarged photos into 1/4” strips, warp the loom with color threads, and weave them back together. The finished piece includes both loom and woven image forming a 3-dimensional photo object.

While working on an earlier project exploring 1960’s tin dollhouses, I began thinking of other toys used to prepare girls for their future as housewives. I remembered the potholder loom I, and many others played with and loved. At this time, I was also scanning photos from my mother’s albums to create an archive. The square pictures and the square loom seemed to connect one to the other, and the idea emerged to combine them.

As Lilian Monk Rösing writes in her essay, Weaving Time, “In ancient Greek, a loom is called ‘histos’; to weave is to tell a story.” I’m interested in unraveling the unspoken details of my childhood and re-telling the story of our family from the vantage point of today. Cutting apart photographs and reassembling them is a repetitive practice. As I create patterns with colored thread and maneuver the canvas under and over, the image is slowly revealed. In these moments, I travel back and forth in time, looking for clues to unravel the past.

Lucy Bohnsack, Untitled (Relic 1)

‘This Work They Call Love’ walks a mile in the shoes of women who take on the job of raising children but are not supplied with the full breadth of resources required. Financial stressors, access to healthcare, and affordable childcare are just a few of the unnecessary roadblocks on the path to raising the next generation in this, ‘The Greatest Country on Earth’. As an exercise, I set out to do my job, to make a photograph, as I would my job as mother, using only the tools at hand and a determination born of necessity. I called upon my local community for volunteers who would sit with me and allow me to witness and photograph them. With digital files in hand but the photo paper being the metaphorical missing resource, I turned to cardboard, plastic bags, scraps of fabric, and a printer not designed to handle any of it. The final product makes visible the hours of work put in to create the finished image; stitched, stapled, pieced, and layered. It memorializes the ingenuity and resilience women employ while fulfilling their work and demand their efforts be seen in the light of day.

Bootsy Holler, Julia - Brain Cancer

CONTAMINATED is a layered exploration of the tens of thousands affected by radiation illnesses and the secrets kept at the Hanford Nuclear site. Hanford produced plutonium for the first nuclear bomb used during WWII. In 1942, my Grandfather arrived on the land as a surveyor and started working for the U.S. Government's Manhattan Project. Contaminated is what has happened to the people and the land in southeastern Washington State. This is where I was born. This is where my family lives.

An undertaking of this magnitude had never been attempted, and the records kept on employees' safety years later were deemed insufficient. The U.S. Department of Labor now has the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA), which began in October 2000. This Act now pays out employees and family survivors with specific illnesses related to working at the Hanford site.

My family, thousands of other employees, locals, and the land have all been affected. In the 1990s, after the Cold War, the Hanford reactors were decommissioned and left behind 53 million gallons of high-level, complicated mixed nuclear waste. To this day, the Hanford Site contains two-thirds of the United States' radioactive waste - and is the most extensive environmental cleanup in the US.

CONTAMINATED is my experience growing up in this highly charged and secretive town and its impact on the people and land. Each unique piece is hand-built from family and friends' stories, pictures, and declassified documents.

Constance Jaeggi, Marisol, Melanie, Nathaly and Stacy

This work considers the Mexican tradition of escaramuza, all-female precision horse riding teams who execute exacting maneuvers while riding sidesaddle at high speed and wearing traditional Mexican attire. Widespread in Mexico, escaramuza is becoming increasingly established in the United States.

While photographing teams across the US, I extensively interviewed the riders. The interviews give a broader sense of the escaramuzas’ experiences as women in charrería culture, and as immigrants, or as first-, second-, or third-generation Americans. The predominantly male national sport of Mexico, charrería emerged from early Mexican cattle ranching activities and was eventually refined and formalized during as a romantic, nationalist expression of lo mexicano (Mexicanness). The escaramuzas speak of the sometimes-frustrating machismo that they must navigate within their sport. In my photographs I seek to respond to this frustration, to capture the grace and dignity of these women, while reckoning with the gendered complexities of escaramuza within the charrería tradition. All the women are photographed in formal escaramuza dress—ornate and handcrafted garments that are in many ways emblematic of the social and cultural dimensions, as well as tensions, in their stories. They present themselves formally, and in this sense suggest a certain rigidity and strictness within the tradition. But this formality also describes the escaramuzas’ immense discipline, skill, and precision as riders. The beauty of their garments is celebratory and expressive, speaking to the individual and their subjectivity, as well as to the profound sense of belonging that the tradition of escaramuza collectively holds for its practitioners.

Owen Davies, Jacob Riis Bathhouse

Light/Mass is an ongoing series of alien urban landscapes found in cities across the United States.

Exploring the overlooked architecture of metropolitan America, I seek to reveal the beautiful strangeness of these monument-like structures standing in familiar environments.

I moved to New York City from England during the Spring of 2020, days before the city shut down. Like many people living in New York during that time, I walked and cycled through the almost empty streets, passing the time and getting a sense of my new home.

I became fascinated with these strange-looking buildings I’d stumble upon, looming suddenly when turning a corner. They felt like distinctly otherworldly structures, alien to the surrounding architecture, yet unnoticed by passersby. I began seeking them out, looking for oddity in a city returning to normal.

The crisp light of New York City influenced my response to these structures; it amplified texture and created new geometry as hard shadows formed on outcrops, angled facades and the ground on which the buildings stood. They took on a monumental appearance, absorbing the sunlight like it was a natural piece of the landscape.

The buildings I photograph were designed by architects and planners who envisioned a bright utopian future for those living in America’s large cities. I prefer not to present a comment on whether this was successful. Instead, I seek to frame them as incredible monuments, dynamic and unsettling, now standing out of place and overlooked.

Jonathan Jasberg, Sailors & The Sphinx

While exploring a labyrinth of winding streets in an off-the-beaten-path neighborhood of Cairo, a man stopped me. He asked, "Why are you taking photographs?" Overwhelmed by the scene, I simply motioned and replied, "Just look at it, it’s beautiful." He looked, then scoffed, "Beautiful?! It’s an old mess," and walked on. This was the first, but not the last time I encountered such reactions as a photographer in Cairo.

Researching Cairo, I found phrases like "Is it safe?", "threat of terrorism" dominating message boards and articles. The general advice was to see the pyramids and museum before moving on to Luxor. However, headlines from a century ago told a different story. In 1925, Cairo was voted "Most beautiful city in the world". Today, it is more commonly associated with the tumultuous era since the 2011 revolution. Nearly a century has passed since 1925, and the remains of this turbulent 100 years mixed with the present day created a unique narrative that I aimed to capture. After losing my job in early 2020, I dedicated much of 2020 and 2021 to documenting this seldom-photographed megacity.

The project's title borrows from an ancient Egyptian proverb: "A Beautiful Thing Is Never Perfect." Through candid photographs, I aim to show moments of joy, sadness, quirkiness, and hope. My goal is to capture the lives of Cairos people, revealing moments that, despite our different backgrounds, we can all relate to and appreciate the shared beauty of life.

A beautiful thing is never perfect

Tira Khan, Ancestral Home

In this project I am both outsider and insider. As a foreigner, I travelled to India and found an unfamiliar place. Yet as part of the Indian diaspora, my trip was a return of sorts: I was invited to dinners, introduced to relatives, and visited my family’s ancestral home.

Rampur is a small city with the highest Muslim population in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous and poorest state. Under British rule, it was a Rohilla Pathan Princely state ruled by a Nawab. In the 1930s, the Nawab sent my grandfather, his physician, to London to continue his medical education. My father was born in London, and I in Boston.

I started photographing this project in 2019, and later returned in 2022. I see myself as both an insider and outsider, and I selected these photographs to emphasize the contrast between interior and exterior space. Many of the homes in Rampur consist of a courtyard surrounded by four walls with bedrooms and a kitchen. Multigenerational families live together inside these enclaves.

Half of these photographs focus on the intimacy of home, and those who have let their guard down in this personal, familial sphere. The rest of the photographs show Rampur’s public space: the street, alleyways, a crumbling palace.

When I first began taking photographs of Rampur my intention was to learn about the city and its residents. Now, my motives may be more complex as I think about my own relationship to this foreign place.

| | |

Andrés Gallego

| | |

Mark Forbes

| | |

Dirk Hardy

| | |

Christos Palios

| | |

Heather Evans Smith

| | |

Astrid Reischwitz

| | |

Kimberly Witham

| | |

Julia Fullerton-Batten

| | |

Kazuaki Koseki

| | |

Xuan Hui Ng

| | |

Matthew Ludak

| | |

Jacques Gautreau

| | |

Jim Hill

| | |

Matt Eich

| | |

Bryan Birks

| | |

Stefanos Paikos

| | |

Aimee McCrory

| | |

Nina Hamberg

| | |

Margo Cooper

| | |

Lisa McCord

| | |

Amy Gaskin

| | |

R.J. Kern

| | |

Mona Bozorgi

| | |

Takeisha Jefferson

| | |

Joseph Kayne

| | |

Raymond Thompson, Jr.

| | |

Anne Berry

| | |

Rachel Portesi

| | |

Colton Rothwell

| | |

Andrea Sarcos

| | |

Sarah Mei Herman

| | |

Yvette Marie Dostatni

| | |

Terri Warpinski

| | |

Katie Shapiro

| | |

Charlotta Hauksdottir

| | |

Seido Kino

| | |

Sander Vos

| | |

Walter Plotnick

| | |

Barbara Strigel

| | |

Kristin Schnell

| | |

Selina Roman

| | |

JP Terlizzi

| | |

Galina Kurlat

| | |

Eli Craven

| | |

Pamela Landau Connolly

| | |

Lucy Bohnsack

| | |

Bootsy Holler

| | |

Constance Jaeggi

| | |

Owen Davies

| | |

Jonathan Jasberg

| | |

Tira Khan